One of my favorite things about living in DC is that there is hardly ever a dull moment. From environmental films and lectures to concerts and readings, I have encountered new and interesting ideas in unexpected places. This past weekend, I found inspiration at the National Gallery of Art, staring at numerous paintings of one of the most unique landscapes on the planet: Venice, Italy. The exhibit on display in the East Wing building showcases the work of Giovanni Canaletto and his contemporaries, who depicted Venetian life in the 18th century.

One of my favorite things about living in DC is that there is hardly ever a dull moment. From environmental films and lectures to concerts and readings, I have encountered new and interesting ideas in unexpected places. This past weekend, I found inspiration at the National Gallery of Art, staring at numerous paintings of one of the most unique landscapes on the planet: Venice, Italy. The exhibit on display in the East Wing building showcases the work of Giovanni Canaletto and his contemporaries, who depicted Venetian life in the 18th century. While moving from painting to painting, I was reminded of two things. First, that these people were inextricably linked to the sea. This was a city whose culture quite literally ebbed and flowed with the tide: goods, food, diseases, visitors, floods, and animals all came and went, weather permitting. Not only did these people live by the sea, but they celebrated by it as well. Many of their festivals followed lunar cycles relating to the tides and how much water was inundating their city. One of their largest celebrations took place on Ascension Day and marked the official marriage between city and sea. Second, I was reminded simply that natural and human landscapes change over time, seemingly drastically.

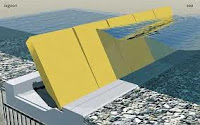

While moving from painting to painting, I was reminded of two things. First, that these people were inextricably linked to the sea. This was a city whose culture quite literally ebbed and flowed with the tide: goods, food, diseases, visitors, floods, and animals all came and went, weather permitting. Not only did these people live by the sea, but they celebrated by it as well. Many of their festivals followed lunar cycles relating to the tides and how much water was inundating their city. One of their largest celebrations took place on Ascension Day and marked the official marriage between city and sea. Second, I was reminded simply that natural and human landscapes change over time, seemingly drastically. While the decorated ships and lavishly dressed Venetian festival attendees have faded with history, two hundred and fifty years have passed and borne a very different connection to the sea through climate change. For years, researchers and concerned members of the international community have been working with the city of Venice to cope with their growing vulnerability to flooding and sea level rise. Because Venice was built on the largest mudflat lagoon in the Mediterranean, the city is also sinking. An article by NPR featuring this conundrum was quick to highlight the positive local attitudes about increased flooding, where many residents have simply taken to moving upstairs! Despite any Venetian nonchalance, the much-debated and ongoing MOSE project aims to save the city by installing 78 underwater floodgates that can rise from the surface according to tidal predictions.

|

| Diagram of the MOSE flood gates |

This massive undertaking is just one example of the urban climate change adaptation projects that will likely dot the coasts in the future. It is not an issue of whether human ingenuity can outsmart nature, but more a dilemma of whether we should battle these situations with technology. In the case of Venice, mitigation efforts are unquestionable and motivated by historical preservation (the unimaginable consequences of inaction being far too great). But considering the fact that landscapes do change over time, how do we decide what aspects of our own cultural or societal heritage to preserve and how do we decide what will have to adapt?

It is moments like these when I remember that it is important to be open-minded and well rounded in our thoughts and explorations. Only diverse experiences can inspire us to think across disciplines to find innovative solutions to resource conflicts and environmental challenges. These tough issues aside, it was an enjoyable afternoon at the museum and I would highly recommend the exhibit to anyone who enjoys thinking about how the past might shed light on how cultures around the world will adapt and change into the future.

Read more about the Venice MOSE project on Wiki.

No comments:

Post a Comment